Be careful what you wish for, right? Sometimes we run headlong toward a dream only to crash into reality. Fortunately, we were young, energized, and eager to tackle the job when it happened. I couldn’t wait to rip everything out of that house that didn’t belong. Beaverboard covered beamed ceilings and featherboard walls. Newer, shallower fireplaces covered deeper ancient ones, wallpaper covered paneling – and black soot covered everything. There was a huge coal fired cooking stove in almost every room, with the familiar hole cut out of original paneling to vent it. Floors were bowed, and original boards lost at the first floor – that awful narrow tongue and groove replaced them. Even those were painted and rotted. In every room the floors leaned toward their sills, which were obviously termite ridden. There were three magnificent doorways on the house, but their original doors were missing. All of the windows were replaced with six over six’s. They were made larger, which cut into the interior woodwork.

There was no heat or plumbing or electric. But that wouldn’t deter us. There were treasures to uncover. And besides, we had just come from a project where, for a year and a half, we had lived with an outhouse in the woodshed and a pump outside for water. We could handle this.

With a ten dollar table saw from a neighbor, a few tools and a lot of gumption, the journey began.

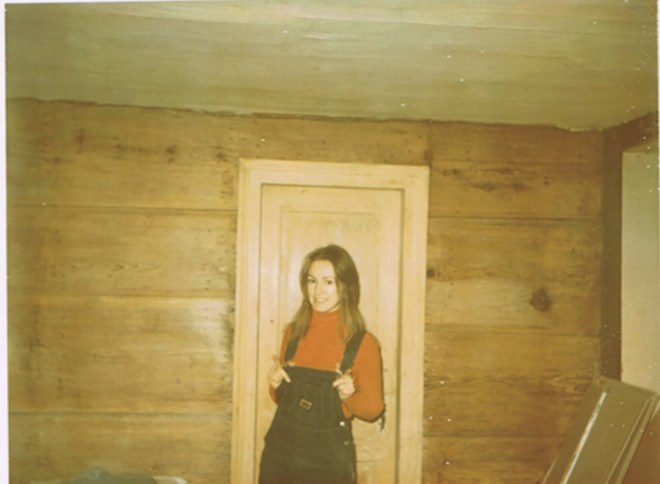

Here are some photos I’ve found. Wish I’d taken more back then – especially with those monster cook stoves – which a local flea market merchant was so kind to take off our hands. No easy task, moving those behemoths.

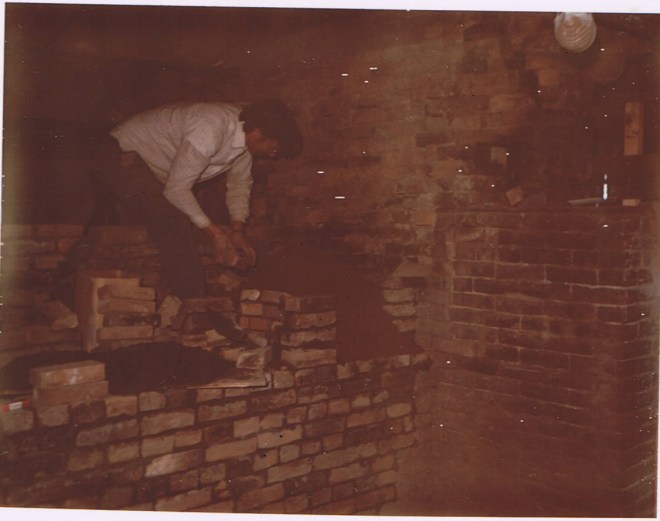

One of the first things we had to put in was, of course, a bathroom. Since our budget didn’t allow for much more than purchasing the house, we would have to do everything. By hand. Here is a shot of the back of the house after taking down the later woodshed. Yes, we’d be going out to the woodshed again, to use the bathroom. But at least this one would be attached and have running water. The big hole in the ground was dug by hand, by Edward, with a little help from a friend. Then he constructed the cinder block foundation, block by mortared block. No matter how much progress you think you’re making with an old house, sometimes, it seems there are as many steps in reverse. The more you uncover, the more work you see ahead of you. Another sill, or rotted post, and everything being connected – another stud to replace, or joist rotted at the end, or girt whose rafters no longer reach…and on it goes.

Thank God for the treasures! And the youth. This photo shows the hole covered and deck on, and the exterior wall of the original 1720 two story ell. A picture’s worth a thousand words – but I’ll probably say them anyway.

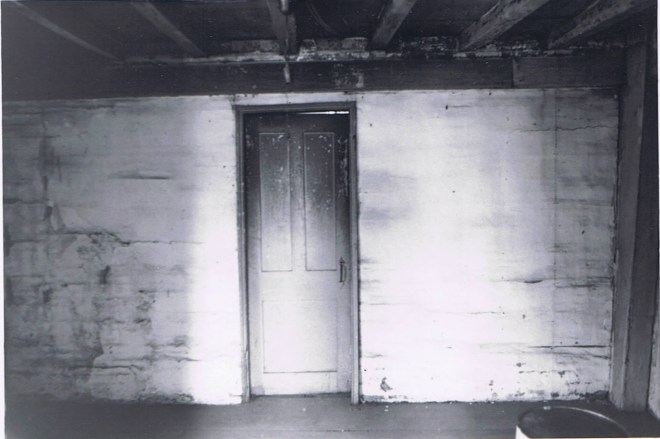

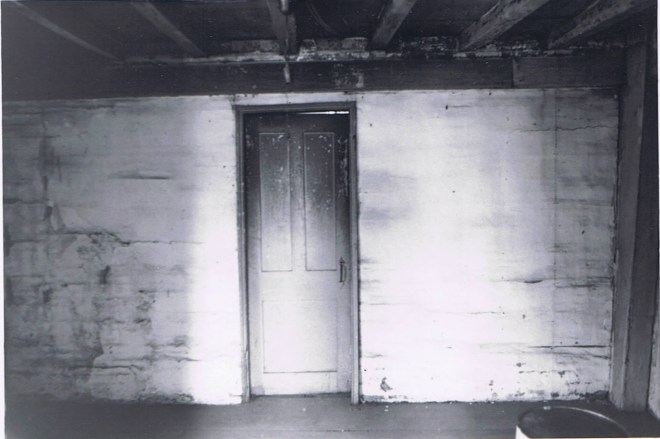

The stair at the back of the house was for one of the many “renters” who lived here over the years. Through the wall sheathing you can see the the back of the original chimney and a bit of the construction of the interior back stair. My favorite part of the whole house – a narrow two panel door in the paneling leads to this primitive back stair with exposed and whitewashed studs and joists. As as you wind up the stair, there’s a landing with a built in bookcase which has aged a deep chestnut color. And on the featherboard wall beside it, there is faded writing, some of which says “war of 1776.” This entire stairwell area is lit by a casement window, boarded up in the photo. Years later, this stair is how our little one would get to her room at night. Instead of candles as in the 18th century, she used a flashlight.

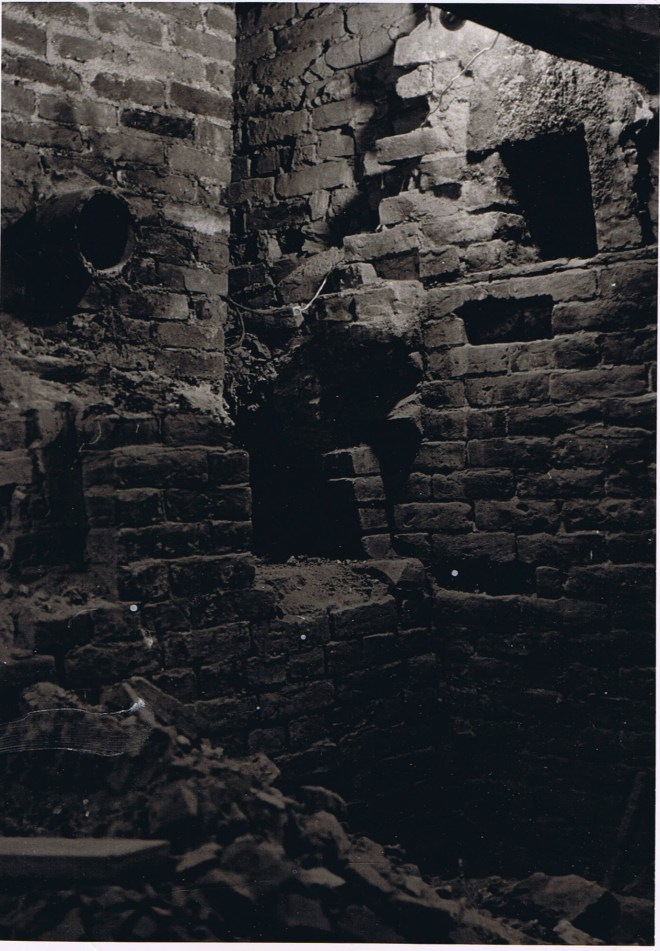

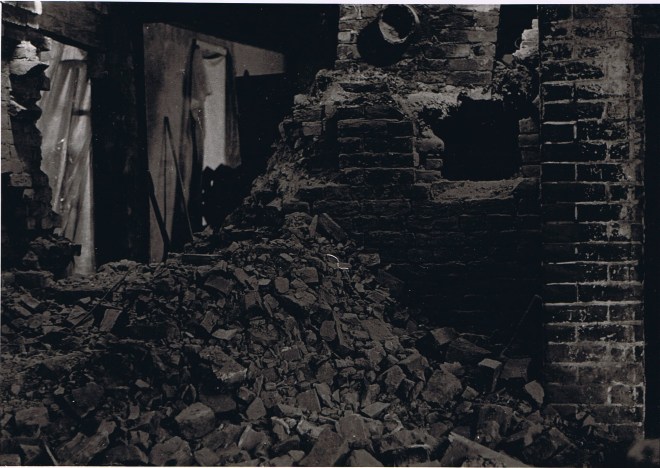

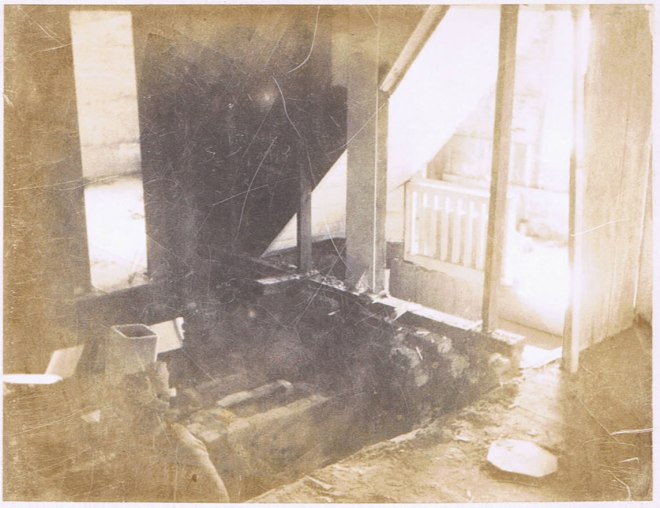

As I said, one thing leads to another. Not until you uncover it all, do you see the extent of the work. Here is the back wall of the lean-to section of the house. By the way, the original two story section of the house was built in 1698, the two story ell was erected in 1720 (we found writing on the joists) and discovered the timbers were re-used, they came from an earlier house. And the lean-to, that makes it a saltbox on one side, was put on around 1760. Meanwhile, we had to remove the entire back wall, replace the girt, re-engage the joists into the new one, replace the sill, and re-stud.

One scary event – this wall was open, with plastic covering it overnight. We were away – and a tornado came through our neck of the woods that day. We thought there’d be nothing left – but fortunately it missed us. I know – it looks like it hit us!

The hole where our future kitchen will be.

Another hole for – guess what? We would add a small kitchen fireplace here, and a paneled wall.

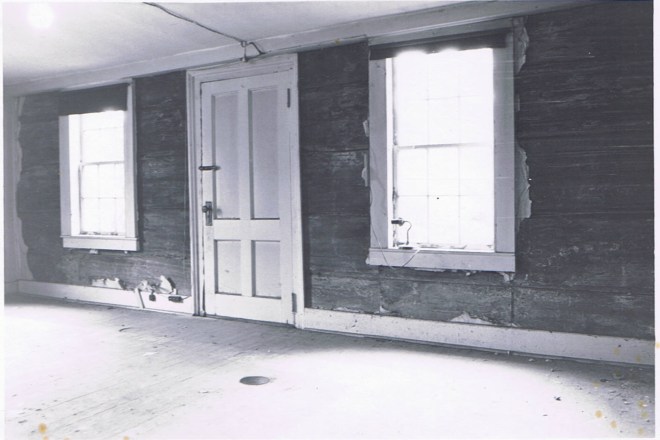

More interior shots. We have our work cut out for us.

1720 addition

Original paneling, with a hole where that darn stove was vented. To the right of this fireplace is the door to the “secret” stair.

A section of the room that was the original kitchen. We’ve removed that old beaver board (forerunner to sheetrock) to expose original horizontal featherboards.

And upstairs:

I love this shot. This is the upstairs front bedroom. It had been divided into two rooms by this wall which was constructed across it from the fireplace to the window. They had to slant the wall, as though they’d built it across and then said “oops!” The original plaster still barely clings to the walls and the whitewashed beams are exposed. Awesome!

On the left you see the backside of that wall that divided up the room – and the bit of fireplace mantel showing! Imagine building a wall right into the decorative mantel?! Note the featherboarding covered with wallpaper – and the gunstock post to the right. Through the hallway you can see the “apartment” they created in the other front room. This room also was divided, painted six different colors, and a crude kitchen added. Here’s an old polaroid I found.

Another room, another stove, another hole. The room may be pink and green and yellow – but it’s all wood. Original featherboard doors are still in their places, opening to tiny closet spaces. The original flooring at the second floor is big and beautiful and wide, and serves as the ceiling of the first floor below.

And all of this, the heaviest, dirtiest work, Edward did alone. I was working during the day to help buy materials, and food for the project. Then nights and weekends were my turn. He was still an aspiring musician/songwriter, and that future hit song was going to pay for the rest of this restoration! Those were the days. One of the many travels in pursuit of a music career took us to London – right after we bought the house. We (and the band) came back with a record deal several months later, well, it was the promise of a deal – with just some fine print to work out. Two weeks after our return, they called to say they could sign only one act right now – and decided to go with an obscure band from Texas – by the name of ZZ Top.

After two more years, spent in Los Angeles, and some interesting times, we came back with our infant daughter, and resumed the restoration – without the help of that million-dollar hit single. Instead, LA handed us another “almost.” While there, the manager spent the advance money, which was to record that single, on a house for himself. It’s a long story.

Needless to say, this old house business was looking like a worthwhile career. We began to do this work for others as well. The rhythm and balance of art and music would serve us well over the years, incorporated into the design and restoration of 18th century architecture. After all, like Goethe said – “Architecture is frozen music.”