While it’s the architecture that lures us to these houses in the first place, it’s discovering the unique stories of the original builders that enliven the experience. From heiress to sea captain, revolutionary soldier to merchant, post rider to pig farmer, all who had a hand in the birth and direction of this experiment, make every visit an adventure. While the home of George Berkeley, 18th century theologian and philosopher, was not open when we were there, it was still a treat to view the unique architecture outside, and impetus to discover the fascinating history of the man responsible for it. A man after my own heart, in his love for art, philosophy and architecture. One of the books in his vast library was by a British architect named Inigo Jones, who had studied the architecture of Palladio in Italy, a style that obviously struck a chord with everyone as it began to be reproduced in England and here in America in the 18th century. George Berkeley thought it the perfect addition to his little cottage as well. Only thing is, to achieve this double doorway on his center chimney house with tiny front hall, one door would have to be false.

I love knowing that someone of his substance was willing to sacrifice convenience for the sake of good design. Good design is everything. And he was willing to live with the minor annoyance that he would never be able to open the door on the left. But it was worth it. I imagine that every time he walked up that pathway his new doorway reminded him of his travels through Europe and the magnificent architecture he had witnessed there. He must have been excited to bring it here to this new land. Thank goodness he did.

Whitehall, what once sat on a hundred acres, now sits on one. That it exists at all is a miracle. Divine intervention, perhaps, since its owner was a famous clergyman. Dean George Berkeley was a minister, teacher, philosopher, one of the leading thinkers of his time, who counted among his friends Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. He was considered one of the big three 18th century philosophers with Locke and Hume. His philosophical work Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge made him famous at home and abroad, he entered Newport in 1729 a celebrity. He was attracted to Newport for its forward thinking and religious freedom. Here he planned to establish a plantation, a home base, from which he could furnish crops and supplies for the college he planned to establish in Bermuda where the sons of the colonists would be trained to become clergymen. The promised funds never materialized, and he would soon return to London, then to his native Ireland where he was appointed Bishop of Cloyne.

His influence in just three short years here, from 1729 to 1731, was grand. Before he left he donated most of the thousand books he brought with him to Yale, the rest to Harvard. The divinity school at Yale was named after him. University of California Berkeley was also named after him, inspired by a line from one of his writings – “Westward the course of empire takes its way…” He influenced King’s College (Columbia) and Brown University. He helped found Newport’s Redwood Library and the Literary and Philosophical Society. He donated his house and land to Yale, the proceeds were to fund scholarships for students studying Greek and Latin. Now a scholar in residence spends a few weeks a year in the apartment upstairs – amidst the books and spirit of the great mind that once inhabited it – how glorious!

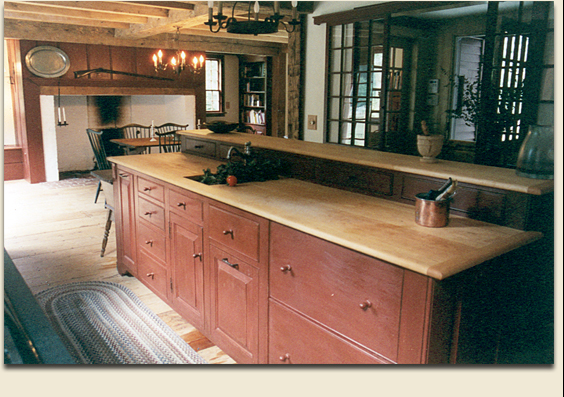

The most important room in a house, is arguably, the kitchen. Not only to satisfy the building inspector who won’t let us live without one anymore, but to satisfy our own creative appetites. We want them to be special, ample, with lots of storage and modern conveniences. Because we love the old, we want them to be traditional and charming, as personal and unique as we are. The trick today is to incorporate all of the new conventions into the old house. The early builder could never have foreseen the evolution of the modern appliance! The ten foot wide hearth, with its iron pots and utensils, and large brick bake oven, was more than ample for the early homeowner’s needs.

The most important room in a house, is arguably, the kitchen. Not only to satisfy the building inspector who won’t let us live without one anymore, but to satisfy our own creative appetites. We want them to be special, ample, with lots of storage and modern conveniences. Because we love the old, we want them to be traditional and charming, as personal and unique as we are. The trick today is to incorporate all of the new conventions into the old house. The early builder could never have foreseen the evolution of the modern appliance! The ten foot wide hearth, with its iron pots and utensils, and large brick bake oven, was more than ample for the early homeowner’s needs.

The end result should be a room that will feel, when you walk into it, like a logical continuation of the old, or at the very least, part of the natural evolution of the earlier house.

The end result should be a room that will feel, when you walk into it, like a logical continuation of the old, or at the very least, part of the natural evolution of the earlier house. But what we do want are classical designs using the same elements that attracted us to the house in the first place. The natural elements that keep us grounded, that remind us we are of the earth and want to remain in touch with it.

But what we do want are classical designs using the same elements that attracted us to the house in the first place. The natural elements that keep us grounded, that remind us we are of the earth and want to remain in touch with it. It should be a pleasant, useful space, whose cabinetry and woodwork do not overwhelm with over-design. It is easy for a homeowner to be seduced by the array of cabinetry and gadgets on display in a kitchen showroom. From the simpler Shaker style to European extravagance, a homeowner can be overwhelmed and end up “picking” a style they like right there on the floor, rather than one that works seamlessly within the context of their own home.

It should be a pleasant, useful space, whose cabinetry and woodwork do not overwhelm with over-design. It is easy for a homeowner to be seduced by the array of cabinetry and gadgets on display in a kitchen showroom. From the simpler Shaker style to European extravagance, a homeowner can be overwhelmed and end up “picking” a style they like right there on the floor, rather than one that works seamlessly within the context of their own home.

Like doctors performing an autopsy, we carefully deconstructed it to see how it was put together. Gently, we knocked out the pins, gingerly tugged at the stiles and rails, slipped the raised panels from their sockets, and studied all of the individual parts. The tenons, the beveled edges of the panels, their sizes, shapes and thickness, the tiny pins, hand carved to be almost square pegs to fit securely into round holes, were all exposed again for the first time in two hundred years. We inspected the pieces with a quiet respect, felt the hand of their maker on the planed surface, noted the secrets of their edges. While we felt a certain irreverence for undoing the past, we sensed a silent approval for the mission on which we were about to embark.

Like doctors performing an autopsy, we carefully deconstructed it to see how it was put together. Gently, we knocked out the pins, gingerly tugged at the stiles and rails, slipped the raised panels from their sockets, and studied all of the individual parts. The tenons, the beveled edges of the panels, their sizes, shapes and thickness, the tiny pins, hand carved to be almost square pegs to fit securely into round holes, were all exposed again for the first time in two hundred years. We inspected the pieces with a quiet respect, felt the hand of their maker on the planed surface, noted the secrets of their edges. While we felt a certain irreverence for undoing the past, we sensed a silent approval for the mission on which we were about to embark.