The most extensive amount of woodwork in an original 18th century house lies directly underfoot. These time worn boards set the tone of every room. Their mellowed color, ancient widths and rich patina hold history in their very grain. At first glance we have an intuitive response, and immediate respect, for the hands that shaped them, the years that mellowed them and the history that gave them character.

Original rosehead nails, embedded at the very edges, hold fast to the joists below with a strength forged by a long forgotten blacksmith. Giant oaks, pitch pines, hemlock and poplar that once stood mighty in the surrounding hills, now lay across miles of New England floors, testaments to the pride and skill of a hardy generation that risked everything to help shape a new world.

Recently, we visited an 18th century home replete with some of the most coveted architectural trim and woodwork of the period. The tiered brownstone steps led to a main entrance surrounded by a magnificent pedimented doorway. The four foot wide paneled Dutch door still had its original brass knocker. The arched fan light above shimmered with wavy glass. Four fluted columns framed the sidelights between them, and an ornately carved Palladian window towered above it all.

It was hard to get past the front door, with so much to take in. The outside adornment is usually a pretty good indicator of what lies within. I could just imagine the trim – paneled staircase, wainscot, moulded cornices and mantels – in their earthen colors, and the flooring, I was certain, would be a glorious pumpkin pine.

The homeowners were excited to share their home. It was a new acquisition, and they were eager to learn more about the treasures they had. They wanted to do the right thing – music to our ears. If only more people would inquire, delve deeper into understanding their old house before taking liberties with it, before changing woodwork, fireplaces, flooring – and even floor plans – on a whim. Why would anyone buy an old house to gut it? To change it? To remove from it all that gave it character and meaning? That’s a rant for another day. We were there to consult about several tasks, but most importantly, flooring.

Over the years the boards had shrunk. In some areas the gaps were as wide as an inch. In some rooms the boards had been painted, but in most they had just been varnished or covered with shellac. They wanted to know how to go about refinishing them and what did we think it would cost. This is the part that is so hard for so many to fathom. The grunt work, the elbow grease involved in reviving an antique floor. You cannot bring in the refinishers from your local flooring showroom. Armed with industrial sanders they can, in one day, or an hour, undo what took three hundred years of time and history to create.

This has to be one of the most heart wrenching scenes – the aftermath of a day of sanding machines gouging across the floors of an antique house. Three hundred years of original character and patina – lost.

Some people are truly sensitive to preservation. They appreciate the past and the reasons to preserve it. Even when they understand that value is maintained by preserving character, integrity, color and finish of original details, sometimes that devil, called convenience and economy, wins in the end.

And that is what would happen here. We advised, they ignored, and that phenomenal antique house now has a lousy new floor. The rosehead nails were sunk – a half inch below the surface! – which makes the floor look like it has holes gouged in it everywhere, and instead of a rich antique color to ground and tone the rooms, a light blond finish screams from below.

Henry Francis Dupont, in decorating Winterthur cautioned that, in good design no one thing in a room should stand out. Newly finished floors stand out. They overwhelm. They scream of their loss. And invariably, the homeowner who has been talked into taking these “convenient” and “economical” measures, regrets it later.

So I urge you, please, to love your old floors, even if they’re covered in stubborn paint or shellac. Strip them carefully, by hand, reveal their color, and enjoy their rich history.

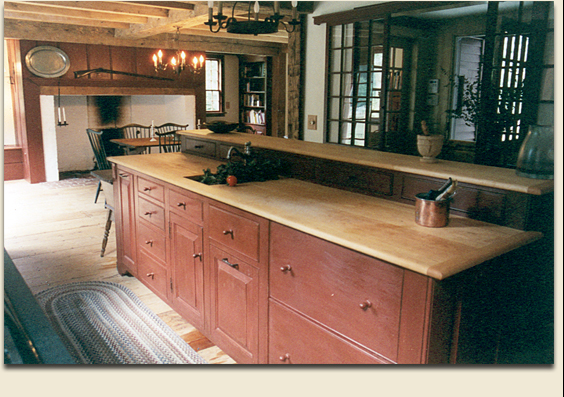

The most important room in a house, is arguably, the kitchen. Not only to satisfy the building inspector who won’t let us live without one anymore, but to satisfy our own creative appetites. We want them to be special, ample, with lots of storage and modern conveniences. Because we love the old, we want them to be traditional and charming, as personal and unique as we are. The trick today is to incorporate all of the new conventions into the old house. The early builder could never have foreseen the evolution of the modern appliance! The ten foot wide hearth, with its iron pots and utensils, and large brick bake oven, was more than ample for the early homeowner’s needs.

The most important room in a house, is arguably, the kitchen. Not only to satisfy the building inspector who won’t let us live without one anymore, but to satisfy our own creative appetites. We want them to be special, ample, with lots of storage and modern conveniences. Because we love the old, we want them to be traditional and charming, as personal and unique as we are. The trick today is to incorporate all of the new conventions into the old house. The early builder could never have foreseen the evolution of the modern appliance! The ten foot wide hearth, with its iron pots and utensils, and large brick bake oven, was more than ample for the early homeowner’s needs.

The end result should be a room that will feel, when you walk into it, like a logical continuation of the old, or at the very least, part of the natural evolution of the earlier house.

The end result should be a room that will feel, when you walk into it, like a logical continuation of the old, or at the very least, part of the natural evolution of the earlier house. But what we do want are classical designs using the same elements that attracted us to the house in the first place. The natural elements that keep us grounded, that remind us we are of the earth and want to remain in touch with it.

But what we do want are classical designs using the same elements that attracted us to the house in the first place. The natural elements that keep us grounded, that remind us we are of the earth and want to remain in touch with it. It should be a pleasant, useful space, whose cabinetry and woodwork do not overwhelm with over-design. It is easy for a homeowner to be seduced by the array of cabinetry and gadgets on display in a kitchen showroom. From the simpler Shaker style to European extravagance, a homeowner can be overwhelmed and end up “picking” a style they like right there on the floor, rather than one that works seamlessly within the context of their own home.

It should be a pleasant, useful space, whose cabinetry and woodwork do not overwhelm with over-design. It is easy for a homeowner to be seduced by the array of cabinetry and gadgets on display in a kitchen showroom. From the simpler Shaker style to European extravagance, a homeowner can be overwhelmed and end up “picking” a style they like right there on the floor, rather than one that works seamlessly within the context of their own home.

Like doctors performing an autopsy, we carefully deconstructed it to see how it was put together. Gently, we knocked out the pins, gingerly tugged at the stiles and rails, slipped the raised panels from their sockets, and studied all of the individual parts. The tenons, the beveled edges of the panels, their sizes, shapes and thickness, the tiny pins, hand carved to be almost square pegs to fit securely into round holes, were all exposed again for the first time in two hundred years. We inspected the pieces with a quiet respect, felt the hand of their maker on the planed surface, noted the secrets of their edges. While we felt a certain irreverence for undoing the past, we sensed a silent approval for the mission on which we were about to embark.

Like doctors performing an autopsy, we carefully deconstructed it to see how it was put together. Gently, we knocked out the pins, gingerly tugged at the stiles and rails, slipped the raised panels from their sockets, and studied all of the individual parts. The tenons, the beveled edges of the panels, their sizes, shapes and thickness, the tiny pins, hand carved to be almost square pegs to fit securely into round holes, were all exposed again for the first time in two hundred years. We inspected the pieces with a quiet respect, felt the hand of their maker on the planed surface, noted the secrets of their edges. While we felt a certain irreverence for undoing the past, we sensed a silent approval for the mission on which we were about to embark.